The Emancipation of Aunt Jemima

- Anneliese Wilson

- Jun 17, 2020

- 3 min read

The plantation has finally burned down and Aunt Jemima has been set free. The only problem? She’s not here to see it.

By now, we've all heard the news that Quaker Oats is planning to rebrand the Aunt Jemima products “to make progress toward racial equality.”

This announcement feels a day late and several dollars short. Considering that Quaker Oats has previously been able to squash a reparations case brought forward by descendants of one of the original brand ambassadors, their announcement comes across as a grand display of virtue signaling. The company has unjustly had 130 years to profit off of Black women’s ingenuity, personhood and spirit.

Two of the original Aunt Jemima brand ambassadors, Nancy Green and Anna Short Harrington, were early recipe developers and demo cooks for the Jemima brand. The magic and grit they put into the product was supposed to equate to fair compensation, but instead it was swagger jacked, mass produced and sold as an authentic down home experience to American households. What makes this particularly insidious is that Nancy Green used what money she did acquire to become an anti-poverty activist, and eventually was laid to rest in an unmarked grave. In essence, Quaker Oats became successful by silencing Black women in the kitchen.

Anna Short Harrington (left) and Nancy Green (right) depicted as Aunt Jemima.

It’s no mistake that the Aunt Jemima caricature was chosen as the face of the brand. Aunt Jemima stems from the racist tradition of minstrel shows mocking the “mammy” found on plantations. "Mammy" is often an older, fat woman with a jolly disposition and an unconditional love for all her “chirruns.” Mammy conjures up romanticized fantasies from the Antebellum era when Black women happily sang in the kitchen and gleefully wiped the spit up of little white children.

The problem with this image is that it paints over the harsh reality. Black women working in plantation kitchens stoked fires and stirred pots at lightning speed so their masters could be well-fed and nourished. All the while, enslaved Black women and their kin likely suffered from hunger and malnutrition. What was once a source of pride in the kitchen became a life sentence.

Plantation cook in the kitchen at Refuge plantation, Camden County, Georgia (ca. 1880)

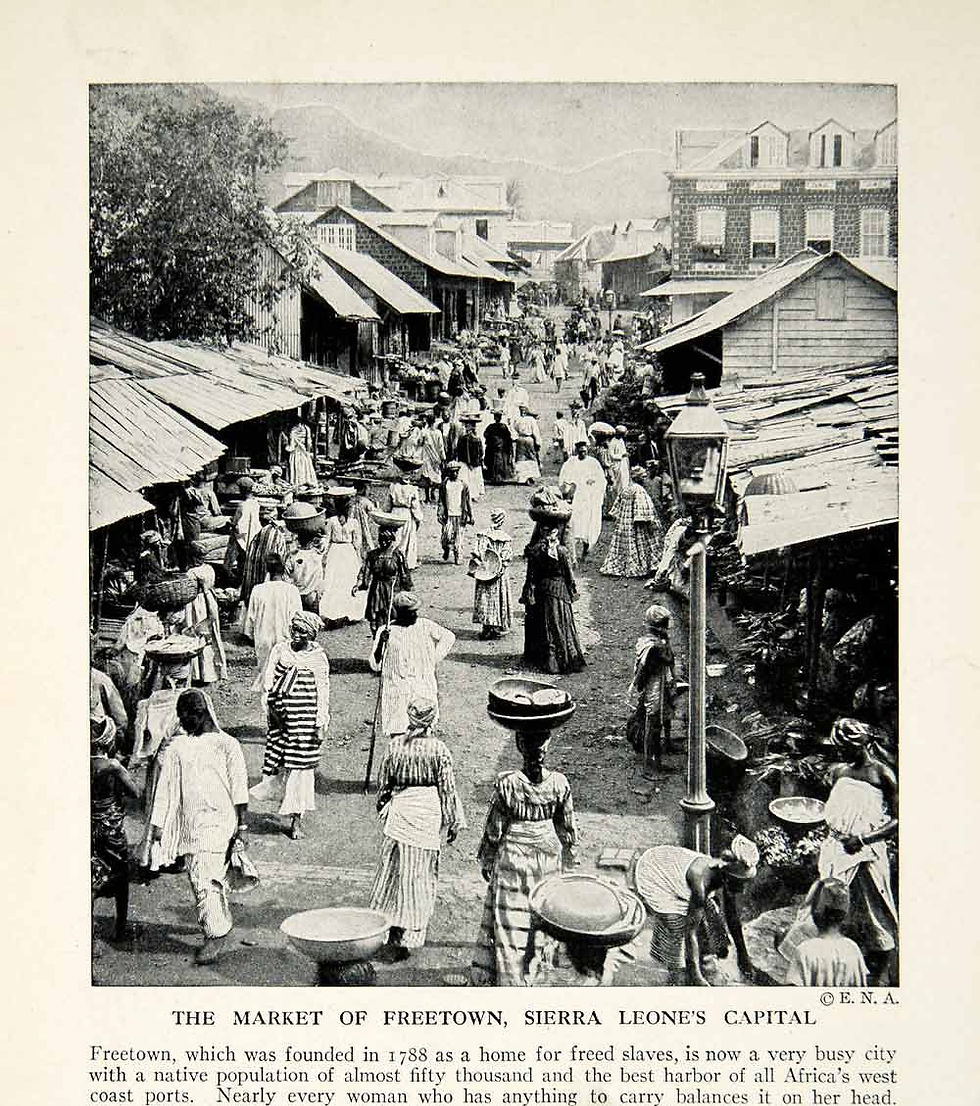

The legacy of Aunt Jemima is disheartening because it bastardizes the important role that Black women had in the food community long before slavery. Back on the continent, women were (and continue to be) rulers of the marketplace. On any given day, you could find a woman selling produce or street food meals. They were affectionately the Mothers of the marketplace that kept society going.

Where Aunt Jemima differs from the Mothers of the marketplace is that she has no agency. Aunt Jemima nourishes others before she nourishes herself. Aunt Jemima is stuck in the kitchen.

For Black women in the food community, it’s important that we have control of our own narrative. There are generations before us that fought tooth and nail to make sure our voices were heard. Taking their food to the streets, they found a way to empower themselves during times that didn't always seem hopeful. When people relied on the "Mammy" stereotype to push us out of the kitchen, women like Flora Mae Hunter and Leah Chase made sure we still had our aprons waiting in the kitchen.

It’s too easy to say that no one wants politics in their pancakes. But when you look closer at the box mix and see that Aunt Jemima’s smile is cracking, you can no longer ignore the problem. For too long, Black women have gone uncredited, uncompensated and unappreciated for their contributions to American food culture.

The cries you currently hear on the streets are the same cries you’ll likely hear in the kitchen. Black women are tired of being silenced and kept behind the scenes. We are no longer willing to wait for our flowers to arrive in our golden years or at our graves. Now more than ever, it’s important to honor and elevate the magic that Black women have contributed to the kitchen.

Comments